Dusty Duffel Bag Found in Italy Reving the Story of a Cape Bretoner Killed in WW II

On most summer afternoons, Michele Facchini won’t leave the Sweltering Hot, low, flat northwest of Ravenna, Italy, with a metal machine.

However, it was here that he made an unexpected connection to Hapa Breton McDonald, a soldier who died in action in 1944.

The 49-year-old Facchini, a second world war researcher and teacher, often spends summer weekends at home, studying Canadian military diaries and subsequent war maps.

On July 6, he took advantage of the mild weather and headed for the outskirts of the city of Russi, near the river Lamone.

There, in December 1944, approximately 10,000 Canadian troops advanced to suppress Nazi forces advancing from northern Italy. His research suggested that the platoon had fought for the field, loaded with ammunition and bombs, the earth seats on the side, as the men climbed the river over the frigid, watery area.

The metal detector of the facchini was removed with the remains of bullets and wrists from exploding bombs. Then the farmer in the world who had done these few things that were gathering dust in the storage room of his houses.

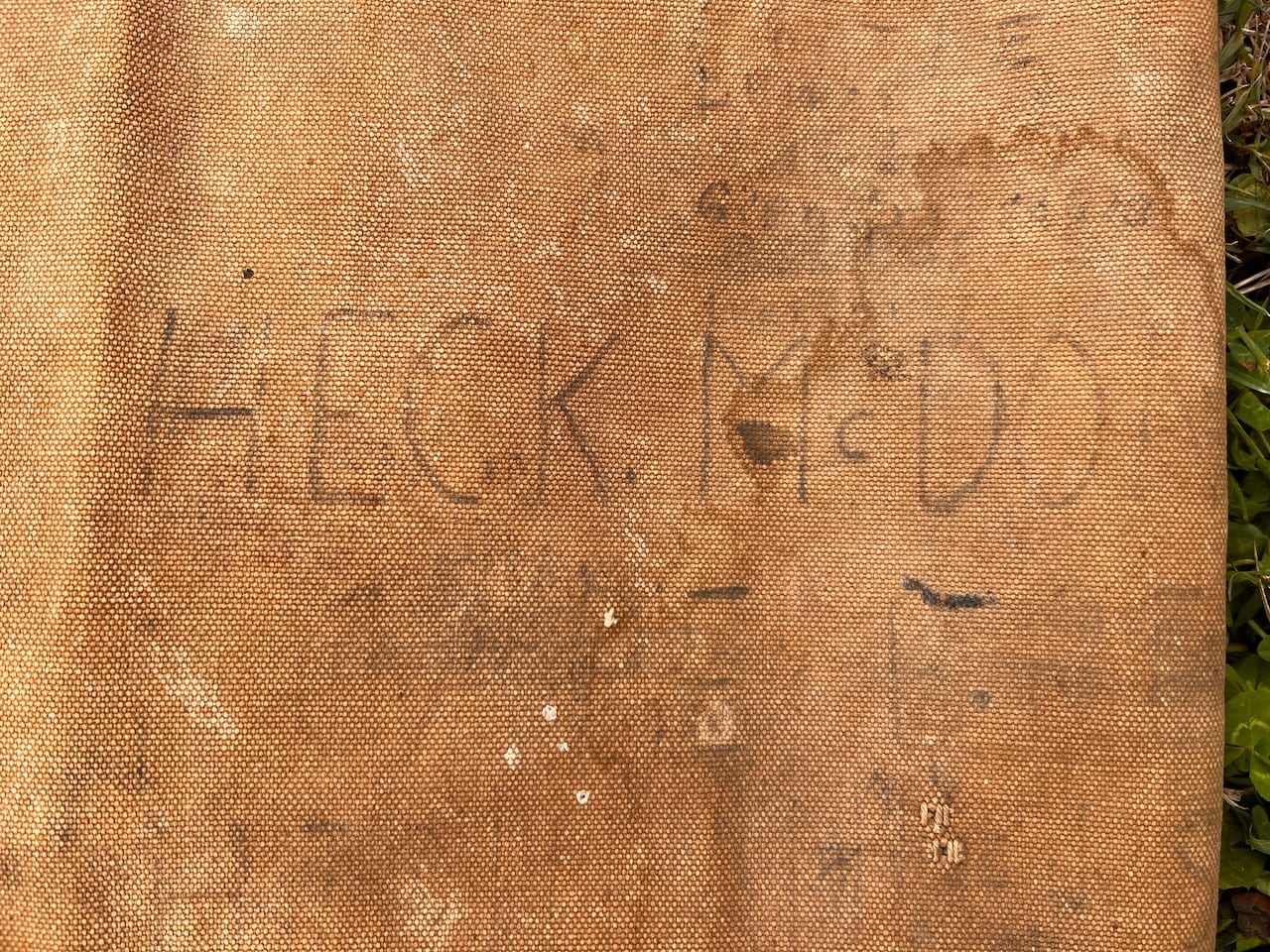

“That’s where I see the duffel bag, the kind soldiers keep their personal effects,” Chchini said. “It’s covered in dirt, but underneath I can make letters that spell out the name and numbers of the organization.”

The accidental discovery could revive a story that went untold for 81 years – and reconnect McDonald with a family that has never forgotten him.

There is no picture of Hector Colin McDonald surviving, but wartime documents paint a picture.

He was a wiry five-nine and 137 pounds. He had hazel eyes and brown eyes. His bearing is marked by “correct” and “correct.” He was the third of six children.

He was a young man who left school in New Aberdeen, Cape Breton at 15 to work in the fields of the Dominion Coal Company, as most of the men in his family did, hoping one day to become an inventor.

Instead, in late 1941, at the age of 25, McDonald appealed to fight in World War II, like thousands of young people, because, as noted in his file, “it was the right thing to do.”

He joined the Northern Nova Novatia Highlanders and continued to fight in the ill-fated battles of the Italian campaign.

This included a combined attack on Sicily, the landing on the Reggio Calabria Mainland, which was damaged in the brutal road at Ortona, and the grinding attempt to pass through Monte Cassiso.

Then came the last – bleak, mud-choked early north to take the lamone river. They were sure it would take two days, but it took 12. In all, 548 Canadians lost their lives liberating Ravenna and the area.

McDonald, a lance-sergeant, noted each of his battles in his duffel bag. Some names still exist. “Sicily. Italy. Ortona. Cassino.” Some have died.

Among the unspecified attacks he survived was the accidental bombing of McDonald’s Our Melity on December 3, caused by outdated intelligence.

A week later, more than a month before his 29th birthday, the Cape Bretoner was killed by a mine planted by retreating German troops on a small bridge over the Lamone River. The date of death was recorded as December 13, 1944, but Fokchini says the date may indicate when his body was found, two days after entering several soldiers.

He was buried with other fallen soldiers in a nearby farmer’s field in a 1946 war cemetery.

When McDonald died, he may have been engaged to Elizabeth Wales, a woman he had met while abroad. Before being sent to the Italian campaign, he had asked for leave to marry her. Among his personal belongings was a rosary that, according to Chataini’s memory, he had given her.

“Her name was Elizabeth Wales and she lived in the mining houses of Glasgow,” said Mariangela Rondinelli, the country’s second world history who founded the Canadian friends who fought and crossed over in Italy. “We know everything about this woman, her father’s name, her address, but we couldn’t find her family.”

Rondinelli and Facchini are part of a small network of World War II investigators who have spent years documenting the stories of Canadian soldiers who fought in the region, often spanning generations and the communities they protected or helped.

One member of the group, raffaella cortese de bosis, helped confirm McDonald’s identity and trace his family – there is no small family with a common name like McDonald.

His search took weeks and eventually led him to his great-grandson, Kim Pyke, a Canadian Armed Forces Veteran in Kingston, Ont.

“You have to be careful when you contact possible relatives,” said Cortese de Bos, “because sometimes someone caused pain to Kim Pyke, he came back immediately, and ‘Hector McDonald was my god.’ That’s when the tears started to flow. ”

“My mother and two brothers are still alive and waiting for breath to see the bag. It’s a good thing.

The ceremony was held in Russina on Saturday with McDonald’s relatives present.

Pyke was unable to make the trip for personal reasons, but his daughter Stacey Jordan, 23, went to Russia to honor the man the family called “Heckie.”

“An adoption like this is an amazing thing in itself,” said Jordan, “being someone in my bloodline, but also coming from a family with a lot of people in the war, both parents, who really hit it off.

Many family members still live in Glace Bay, just a few doors down from Hector’s home in what used to be a housing mine, she said.

In a moment of spontaneity, another young relative, Cain Chaisild McDonald, 14, of Creston, BC, had just delivered homework to Hector when the duffel bag was nearby.

“I was happy and disappointed at the same time because I could put a duffel bag in the report,” the findings said. “But it was really cool that my report got out and a month later they found his bag.”

Facchini calls the discovery 81 years after the death of Hector McDonald “a singular stubbornness.”

“For me, it’s not about anything,” he said. “I never go to flea markets looking for parpaphernalia.

“To the men who suffered, who did and who gave so much. This is not just a duffel bag.”

Many stories