The validity of Brazil’s climate was tested by searching for oil on the Amazon coast

On a river dock in Oiapoque, a small town in the north of Brazil, Cleidiney Ribeiro hits his riverboat on the water.

He says: “Progress is coming to Oiapoque, as it takes out an hour and a half where the river meets the Atlantic Ocean.

Brazil’s oil company Petrobras has it He just kissed the target dig 170 kilometers of the Amazonian coast, just as Brazil opens the world’s largest climate conference in Belém, Cop30.

In contrast, the President of Brazil, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva told world leaders on Friday, “The world no longer supports a development model based on the extensive use of fossil fuels.”

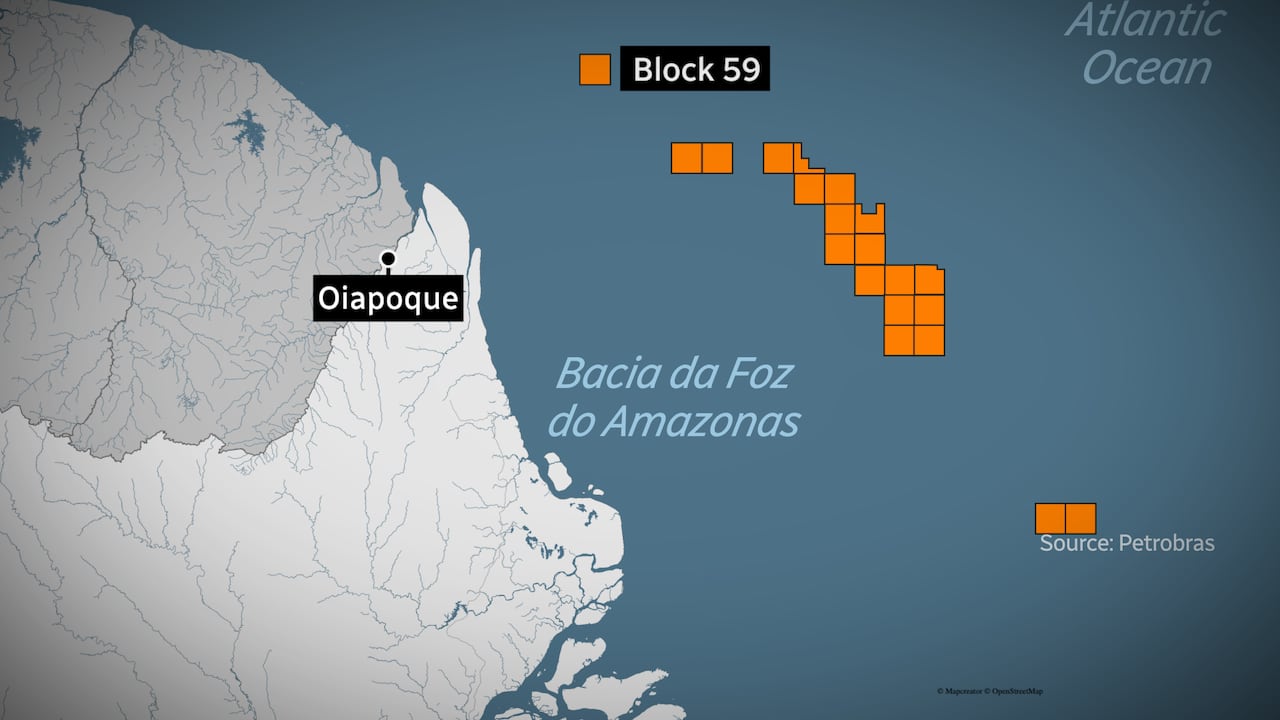

But his Government is on the line of another oil, if the deposits are confirmed in the Foz do Amazonas basin, part of which is 500 kilometers from the Amazon River.

“It’s a big problem,” said Suety Araújo, a public policy coordinator for Brazil’s climate.

Brazil is already a major oil producer – in great size – And Araújo said “the government’s decision to raise this product in the middle of the climate … is absurd.”

Lula wants to change the power of Cop30

Starting Monday, Belém hosted tens of thousands of visitors and spectators in the Amazon City of 1.3 million. Accommodation is scarce – Two cruise ships went ashore to accommodate other guests and the President stayed on board a luxury yacht.

Cop30 will try to strike a new impetus to deal with the emission of fossil fuels in the planet-warming, and encourage countries that move quickly to sustainable sources of energy.

“Brazil is not afraid to discuss the energy transition,” President Lula said at a summit of leaders, pledging to use some of its oil revenues to support it.

But more than a thousand kilometers north, in Oiapoque, the pressure is fat; Black gold, which can transform one of Brazil’s most disadvantaged regions, according to the government.

Hanging on to oil deposits

“We all hope that the oil is there,” said Romeu Costa, who manages the small airport of Oiapoque, which mainly serves medical flights and the oil sector, without air traffic at the moment.

“It’s going to improve the city,” Costa said, adding that real estate speculation is already growing in the city of 27,000.

Twice a day now, a few ten workers fly from the cities in the south and south, and transfer the helicopters to go out to the drilling ship.

Petrobras has 59 block rights, so far the only offshore area licensed to drill and confirm the size of deep oil deposits. But in an auction last June, the government awarded another 19 oil blocks foz do amazonas bastin to companies including Exxon Mobil, Chevron and the China Consortium. Companies must apply for an inspection license.

Petrobras has spent ten years working on a program of exploration and environmental testing, including building a large hospital, a field hospital in New OIAPOQUE to obtain permits. Its efforts were rewarded just two weeks before the Cop30 climate talks.

“It is a moment of admiration, of our victory, of our work, and of our responsibility to the country and the environment,” said Wagner Fernandes, who represents the oil workers’ union and works for Petrobras.

‘Winning ticket’: Minister of Energy

The deposit in Brazil’s Margial Margin can be large, 30 million barrels of oil available, according to ANP, the National Agency of Petroleum, natural gas and biofuels.

Brazil’s energy minister called it a “winning ticket” that could create tens of thousands of jobs and tackle poverty in the region.

But future drilling, if allowed, could enter the Amazon River.

Protests last summer failed to stop the latest oil auction.

“I’m very worried,” said Sueal Araújo, who previously worked for the State Environmental Regulator Ibama, and refused to issue a permit to explore at full capacity in the nearby block in 2019.

Brazil’s state-owned oil company, Petrobras, has begun drilling for oil in the Amazon Rain Forest, raising questions about its climate sustainability. CBC’s International Climate Change Correspondent Susan Ormiston traveled there on the eve of the Cop30 Climate Summit in the region to see the political climate and oil exploitation on the coast.

“It is a fragile region and they will have problems because even if they don’t have accidents, oil production always produces a kind of permanent pollution, silent pollution.”

Indigenous Communities Rally is controversial

A 20-minute drive outside OIAPOQUE, through the Amazon rainforest, the indigenous tribes live on the culupi river in concessions that were successively adopted by Brazil in 2002.

Chief Wagner karipuna says that they were not shown their inclusion in the oil license, which they feared could endanger the waterways and the land.

“If it was due to leakage, the water has no boundary …. it will pollute our river, our fish, game, birds, everything will suffer,” he said.

At a rally last week, more than 50 indigenous leaders from Oiapoque signed a letter opposing the development, demanding an official meeting with Petrobras’ top representatives.

Karipuna says he doubts that the job offer will come to them.

“You need to have a higher education… To work for petrobras, and we indigenous people don’t have that. The government is deceiving us with false promises,” said Karipuna.

Traditional groups are preparing a large demonstration in the Cop30 area of Belém to attract international attention and put pressure on Brazil.

“I understand it’s hard not to see [Brazil’s position] as an unpleasant thing. We like simple things, yes or no, right or wrong, “said Heloisa,” said Heloisa, “said Heloisa Borges from Rio de Janeiro. She is director of oil, gas, and biofuels research at the eper research company.

“We will still need a certain amount of oil and gas in 2050,” he said, explaining the International Energy Agency’s estimate that in 20 years the world will need between 24 and 55 barrels per day.

“Just because we think we don’t want it, doesn’t mean we won’t need it,” Borges said, adding that Petrobras has a “Social License” in Brazil.

“Brazil is very proud of its oil and gas industry. Petrobras is the company in the popular imagination of all Brazilians.”

In OIAPOQUE, there is enthusiasm, but not everywhere, said Estafany Furtado, who works for IEPÉ, an organization that helps traditional groups in the north.

“Those who are against [the drilling] At the moment he is suffering from threats from the political class and the people who are interested. I personally have faced some threats,” he said.

Two years ago at Cop28 in Dubai, almost 200 countries agreed to “switch” from fossil fuels. Since then many countries including Brazil and Canada have reached record oil production.

President Lula calls Belém and gathers “the police.” His critics say, The world truth is that the world has recently consumed vegetable oil and the warming of the planet is still rising around the world, although not as fast as before. It is a big challenge for President Lula and the 50,000 international visitors waiting in Belém.